The Little Town That Could

Following a train derailment and toxic leak, East Palestine, Ohio is short on answers but high on determination.

The residents of East Palestine, Ohio don’t want the country’s pity; they just want their concerns to be addressed. One resident shouted that sentiment amid cheers from a large crowd that filled the East Palestine High School gym for a town hall Tuesday evening. The goal of the event was to bring together a community reeling from a train derailment and the release of vinyl chloride and other potentially harmful chemicals earlier this month.

(Get caught up on the story by reading this article.)

“This could have happened to thousands of other communities like ours. We are not a poor, unclassy community,” the East Palestine resident said, facing dozens of reporters and camera crews. “We are a community that a disaster happened to and we didn’t know how to respond to it. So when you’re reporting this, please don’t say that we’re this poor community, woe is us. We just want answers.”

Residents didn’t get answers from the one source they most hoped to address: Norfolk Southern. The railroad company at the center of the train derailment and subsequent chemical release along the tracks that run through town failed to send a representative to the meeting, due to “safety concerns.” The irony was not lost on the crowd in the high school gym, several of whom shouted, “What about our safety?”

Many people who live in East Palestine and neighboring towns are frustrated by a lack of communication with Norfolk Southern as well as silence from the federal government. On Wednesday, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine asked White House officials for federal assistance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Health and Emergency Response Team and the CDC. Despite ongoing efforts to secure federal disaster assistance, Gov. DeWine says he has been told by FEMA that Ohio is not eligible at this time.

DeWine was not present at the town hall, but he has been making frequent visits to East Palestine and offering updates on things like air and water quality. Just a few days ago, he said during a press conference that the train cars carrying toxic materials were marked as non-hazardous, so local officials weren’t notified. “Frankly, if this is true, this is absurd and we need to look at this,” DeWine said. “We should know when we have trains carrying hazardous materials that are going through the state of Ohio.”

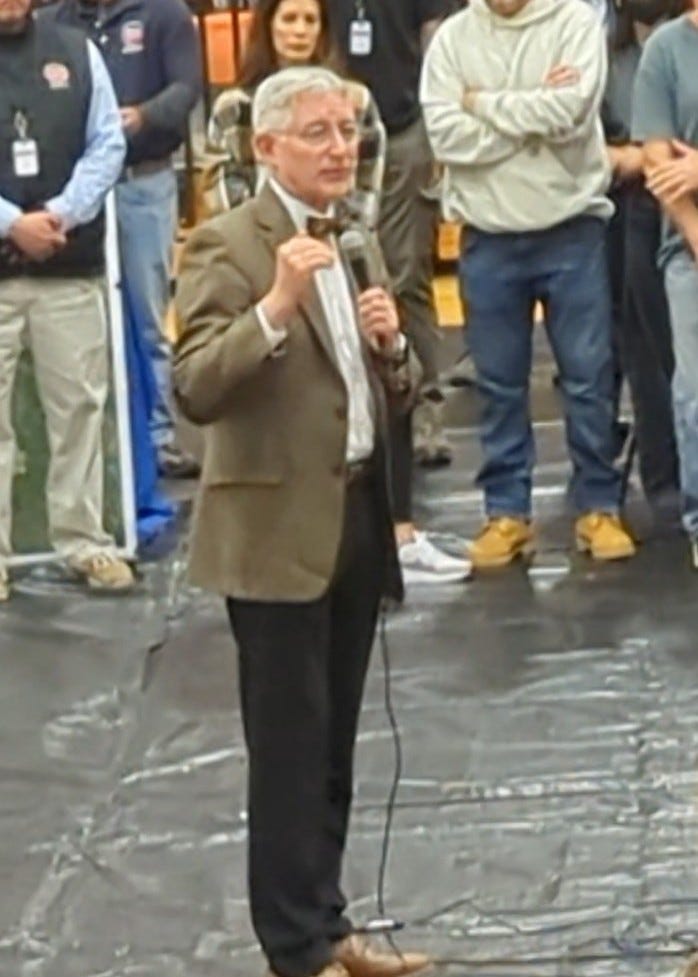

Bill Johnson, Representative for Ohio’s 6th Congressional District, which includes East Palestine, attended the town hall and promised to speak on behalf of his constituents affected by recent events. Newly elected U.S. Senator J.D. Vance was scheduled to arrive in East Palestine on Wednesday. Residents want more, like an acknowledgement that Norfolk Southern has long been cutting safety corners while making big profits. And that those cuts directly impacted the community.

East Palestine (pronounced pal-uh-STEEN) sits along swaths of farmland about 30 minutes south of Youngstown and a stone’s throw from the Pennsylvania border. The town of about 5,000 people tends to have deep roots in the community, with generations of families often living in proximity to each other. This is an unpretentious, neighborly group that isn’t used to the national spotlight.

At the town hall, East Palestine Mayor Trent Conaway looked like he might have just come off his shift on the assembly line. He was dressed casually, almost sloppily, but that only added to his everyman personality. “I wasn’t built for this,” he admitted to reporters before the town hall kicked off. Nevertheless, he took charge as he stood in the middle of the school gymnasium and faced thousands of his residents.

With no microphone available, and wanting to be sure that everyone could hear him, the mayor wandered off and then reappeared with a bullhorn. (Eventually, he was given a microphone.) “This isn’t about me. This isn’t about you,” he bellowed into the bullhorn. “It’s about us as a whole.” He said he knows people are sick of the bulls**t on social media. Everyone has questions, Conaway added, and the experts assembled at the town hall would try to answer them.

Questions ranged from, “How was it determined that only people within a one-mile radius of the toxic site should evacuate?” (That was based on guidelines from the Department of Transportation Emergency Response) to, “How do I know that the smell (coming from the creek) isn’t hurting me?” (Testing thus far shows no dangerous levels of toxins in the air or water.)

Experts from the Ohio Division of Wildlife noted that while many fish in the creek died early on, they have since repopulated. That was met with some skepticism from the crowd. Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff, director of the Ohio Department of Health, reassured residents that initial health issues like headaches, a sore throat or rashes shouldn’t linger. But no expert could convince residents that there might not be health or environmental issues down the road. The truth is, since water-and air-quality levels look good, East Palestine could very well be in the clear; however, no one knows what could happen next year or 20 years from now.

Mayor Conaway said that Norfolk Southern “did us wrong,” although the company is in the midst of an ongoing plan for cleanup of the derailed cars. He added that the company assured him everyone living within the 44413 area code, which encompasses East Palestine and Unity, Ohio, will receive a $1,000 check. After some hissing in the crowd, the mayor said that was just the beginning of what Norfolk Southern would hopefully do to compensate the area.

One resident suggested hounding Norfolk Southern like she did to get something done. She said her property is seven feet from the creek, and she didn’t feel safe, even after she was told she could return following a mandatory evacuation. After badgering Norfolk Southern, the company sent a topologist to her home, who tested her soil. Following the results, a representative from Norfolk Southern told the woman it was unsafe for her to live in her home. She also said the company offered to pay her moving expenses and the first and last month’s rent of wherever she moved. (This information has not been confirmed.)

“Why can’t all of these other people here get the same attention,” the woman said, as she waved her hand in front of her fellow residents. “How many of them are sleeping in their houses because they didn’t throw a fit like I did?

After about 90 minutes of noisy but civil discussions, attendees slowly filed out of the gym. Maybe all of their questions hadn’t been answered. At least they joined together as a community and tried to help each other out.

The night sky sparkled with stars as people walked past the high school football field towards their cars or houses. The air had an earthy smell, as it often does on a mild winter night in a bucolic town. A train whistle blew in the background, a sound that would hardly be noticed under ordinary circumstances. How this community longs to be ordinary once again.

The people there are so underserved and deserve better. From the handling of the "controlled burn" to the response by the railroad. NS has a history of not doing right by the communities they affect, as last year in Sandusky a less toxic derailment still has not seen reimbursement to the city for costs associated with it. There were ways to deal with this that would have had a lower environmental impact, but it would have affected the bottom line of the railroad so they went with the cheap route (which might have involved closing the line longer to remove the toxic chemicals). This almost sounds like Love Canal, Three Mile Island, and other disasters all over again.

Excellent